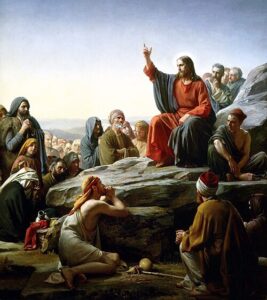

Throughout the history of Christianity, faith has never been understood as an intimate refuge reserved for individual conscience. From its apostolic origins, the Christian experience has been lived as a personal encounter with Christ which, by its very nature, tends to become visible, shared, and communal. Believing has always meant belonging, walking with others, and assuming a common responsibility in the mission.

Throughout the history of Christianity, faith has never been understood as an intimate refuge reserved for individual conscience. From its apostolic origins, the Christian experience has been lived as a personal encounter with Christ which, by its very nature, tends to become visible, shared, and communal. Believing has always meant belonging, walking with others, and assuming a common responsibility in the mission.

St. Paul expressed this with an image that remains decisive: the Church as the Body of Christ. It is this same Church that preaches with conviction this truth that runs diametrically through the entire Christian tradition: personal conversion, while indispensable, is not exhausted in itself. It needs a communal configuration that sustains it, makes it grow, and projects it historically. Faith, to be fully Christian, calls for communion and mission.

Over the centuries, this awareness gave rise to multiple historical forms of Christianity. All of them were attempts—always conditioned by their time—to integrate faith, culture, and social life. None was perfect or definitive, but all responded to the same evangelical intuition: Christianity cannot be lived apart from history or from the concrete environments where human life unfolds.

A new challenge in a fragmented context

In the age in which we live, marked by cultural fragmentation and the progressive privatization of religion, this question takes on priority from a profound discernment. Faith today runs the risk of becoming an isolated experience, devoid of the community, formative, and missionary processes that give it consistency and projection.

In the age in which we live, marked by cultural fragmentation and the progressive privatization of religion, this question takes on priority from a profound discernment. Faith today runs the risk of becoming an isolated experience, devoid of the community, formative, and missionary processes that give it consistency and projection.

It is no coincidence that recent Magisterium has strongly insisted on this point. Paul VI, in Evangelii Nuntiandi, warned that evangelization cannot be reduced to a verbal proclamation or superficial adherence, but must generate people and communities capable of transforming criteria, values, and ways of life from within. Evangelizing, he said, is reaching and transforming environments.

John Paul II deepened this insight by affirming that the laity, by their specific vocation, are called to be protagonists of the Church’s mission in the world, not as delegates of the clergy, but as witnesses who live their faith in temporal realities (Christifideles Laici). Faith, when it is authentic, does not withdraw: it incarnates itself.

Processes, not events: a faith that is sustained and transmitted

From this perspective, attempts are being made to situate the various ecclesial realities which, with different styles, emphases, and charisms, are seeking to structure the Christian experience in ordinary life, integrating in some way the first proclamation with formation and never leaving aside accompaniment. It is not a question of reconstructing historical models of Christianity or generating parallel structures, but of articulating processes that help Christians to live their faith in a coherent, mature, and missionary way in the concrete environments where they live their lives. What we have always called “being leaven in our environments.”

From this perspective, attempts are being made to situate the various ecclesial realities which, with different styles, emphases, and charisms, are seeking to structure the Christian experience in ordinary life, integrating in some way the first proclamation with formation and never leaving aside accompaniment. It is not a question of reconstructing historical models of Christianity or generating parallel structures, but of articulating processes that help Christians to live their faith in a coherent, mature, and missionary way in the concrete environments where they live their lives. What we have always called “being leaven in our environments.”

Pope Francis had taken up this perspective with missionary zeal and momentum. In Evangelii Gaudium, he insisted that the Church is called to be a Church that goes forth, capable of initiating processes rather than occupying spaces, and of trusting in the action of the Spirit who acts in history through specific people. He emphasized the message that in no case is the new evangelization a strategy, but rather a pastoral conversion that places the person, the community, and the mission at the center.

Lay people at the heart of the world, Church in communion

In this context, the role of the laity in today’s world appears with particular clarity. Not as executors of intra-ecclesial tasks, but as ecclesial subjects called to live and witness to the Gospel in the family, at work, in culture, and in social and political life. Wherever the day-to-day life of society is played out, in everyday decisions, wherever environments are shaped, the Christian faith is called to become life.

In this context, the role of the laity in today’s world appears with particular clarity. Not as executors of intra-ecclesial tasks, but as ecclesial subjects called to live and witness to the Gospel in the family, at work, in culture, and in social and political life. Wherever the day-to-day life of society is played out, in everyday decisions, wherever environments are shaped, the Christian faith is called to become life.

All this without ever losing sight of something that, although well known, is no less essential: ecclesiality. No evangelizing initiative is authentic if it is separated from communion with the Church, from listening to the Magisterium, and from pastoral discernment. Missionary fruitfulness does not come from individualism or self-referential projects, but from fidelity to the Gospel lived in communion. The fundamental role of the laity must arise from a total conviction of co-responsibility for the mission and, therefore, for the salvation of the world.

In short, the history and present of the Church converge in the same conviction: faith that does not become part of the community weakens; faith that is embodied in ordinary life becomes fruitful. These are times of change and challenge, times of movements. Staticity cannot be a visible or invisible characteristic of the Church. Today, in every corner of Christianity around the world, there is an open and hopeful call to all lay people who wish to live their Christian vocation with authenticity and commitment in the heart of the world.